Herculaneum V.15. Casa del Bicentenario or House of the Bicentenary.

Excavated 1937-38.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Plan of upper and lower floors

This house owes its modern name to the fact that its excavation was started in 1938, which was two hundred years after the beginning of excavations in Herculaneum in 1738. It occupies a wide area of the northern section of the insula. The entrance at number 15 on the south side of Decumanus Maximus was in a privileged position in respect to the public zone of the city, with another large house (still unexcavated) on its northern side, nearly opposite.

While bearing the signs of the transformations suffered over time, it has retained as a whole the appearance of a stately residence of considerable proportions.

See Pesando, F. and Guidobaldi, M.P. (2006). Pompei, Oplontis, Ercolano, Stabiae. Editori Laterza, (p.352)

Originally, this house had been the noblest and richest dwelling in this insula.

However, in its last years it underwent the same transformation that has been seen in many other private houses.

The whole ground floor still preserved the traditional plan of a grand roman house, whereas the dwelling quarters on the upper floor of the portico appear very humble.

In the last years of the city, it is thought that they were no longer reserved for the families of servants but had become rented lodgings.

When the ground floor was deprived of its fittings and abandoned by its rich owners, there was no longer a need for servants and their families.

These rooms on the upper floor could have been divided into several apartments and rented to modest artisans or merchants.

See Maiuri, Amedeo, (1977). Herculaneum. 7th English ed, of Guide books to the Museums Galleries and Monuments of Italy, No.53 (p.46-7).

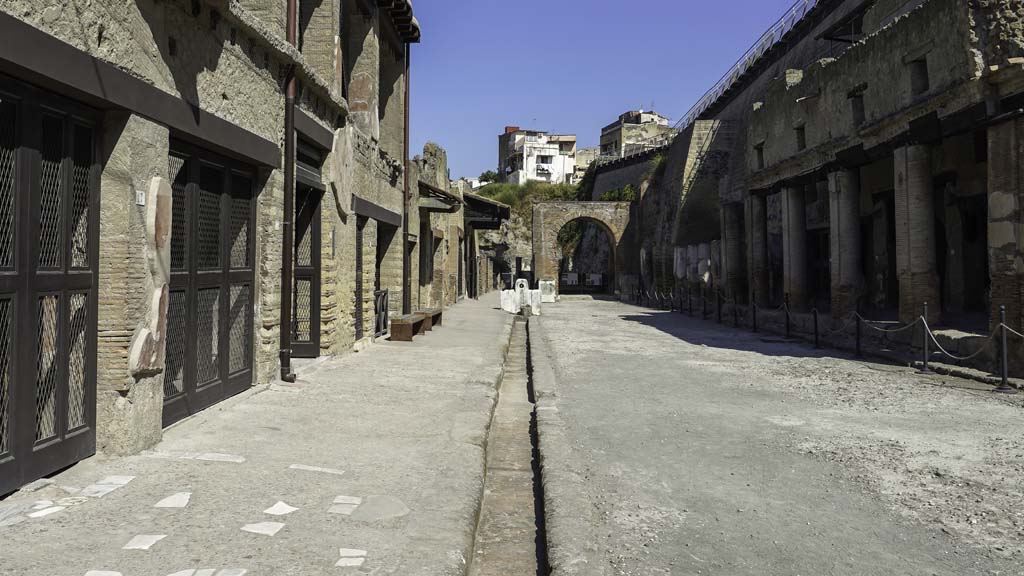

V.15 Herculaneum, August 2021.

Looking

west on Decumanus Maximus, with open entrance doorway, on left. Photo courtesy

of Robert Hanson.

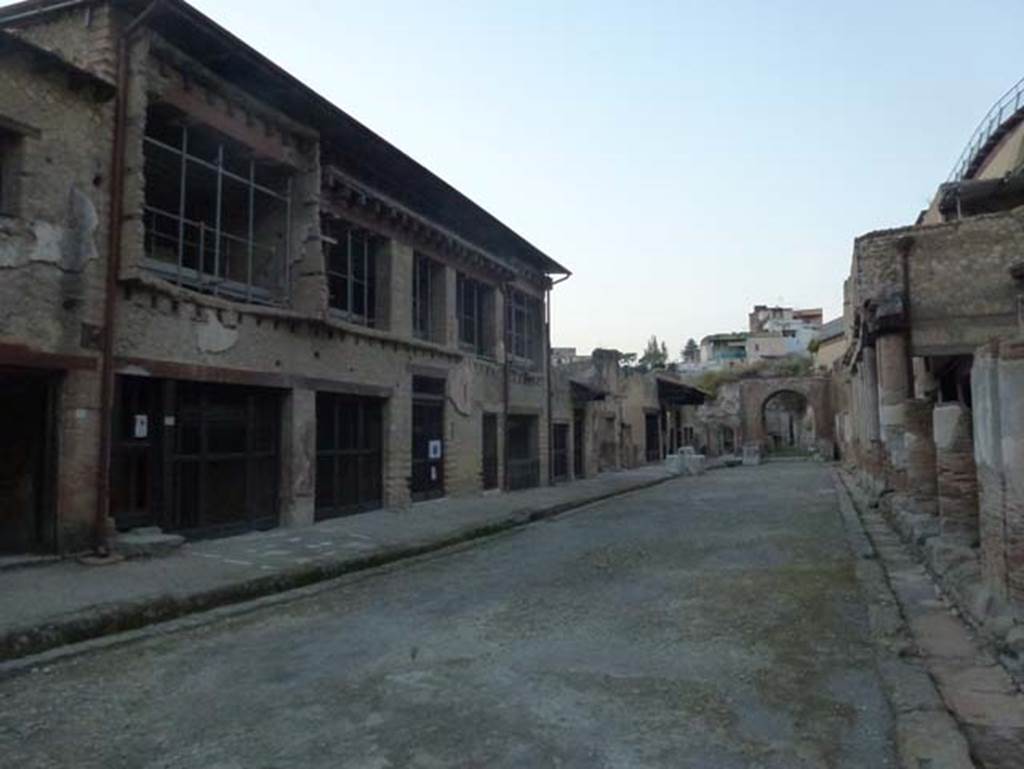

V.15 Herculaneum, October 2020.

Looking towards open doorway on south side of Decumanus Maximus. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

V.15 Herculaneum, October 2019. The tall doorway of V.15 is open. The house was reopened to the public on the 24th October 2019.

Photograph courtesy of MiBAC. Use subject to Creative Commons - Attribuzione - versione 3.0.

V.15 Herculaneum, August 2013.

Looking south-west from Decumanus Maximus towards insula, with V.15 the doorway in the centre. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

Insula V, Herculaneum. 22 Sept. 2014. Looking S-W from the Decumanus to Insula V, doorways V.19

to V.12.

Photo courtesy

of Larry Turner.

Insula V, Herculaneum. 11 April 1977. Looking S-W from the Decumanus Maximus to Insula V,

doorways V18, 17, 16, 15, 14, 13 (L to R).

Photo courtesy

of Larry Turner.

The large House of the Bicentenary can be seen on the left, and nearly opposite under the portico is another large house, which is still unexcavated.

Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

Decumanus Maximus,

Herculaneum, 4th

December 1971.

Entrance

doorways to V.17/16/15,

Casa del Bicentenario (narrower taller doorway. left of centre), and 14/13.

Looking

south-west towards south side of Decumanus Maximus.

Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer, from Dr George Fay’s slides collection.

Decumanus Maximus, south side, Herculaneum, June 2011. Looking east along north side of Insula V.

The doorway to V.15

is the taller one in the centre of the photo. Photo courtesy

of Sera Baker.

V.17, 16 and 15, on right, Herculaneum, May 2006. Entrance doorway to House of the Bicentenary, on right.

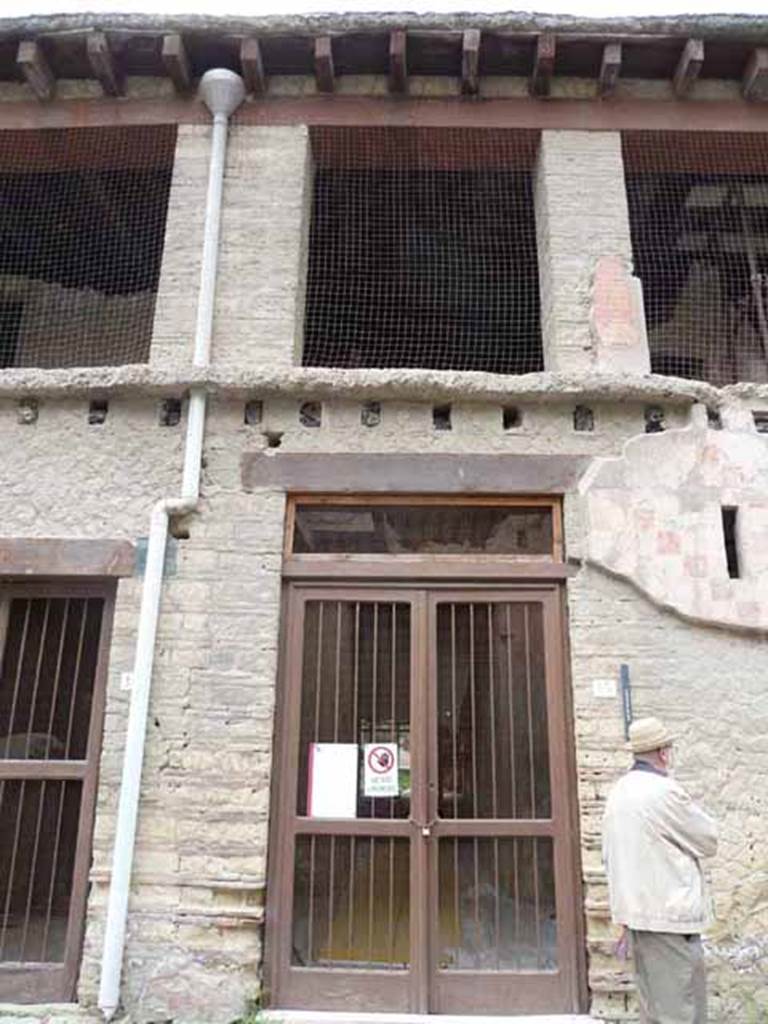

V.15 Herculaneum, September 2015. Entrance doorway.

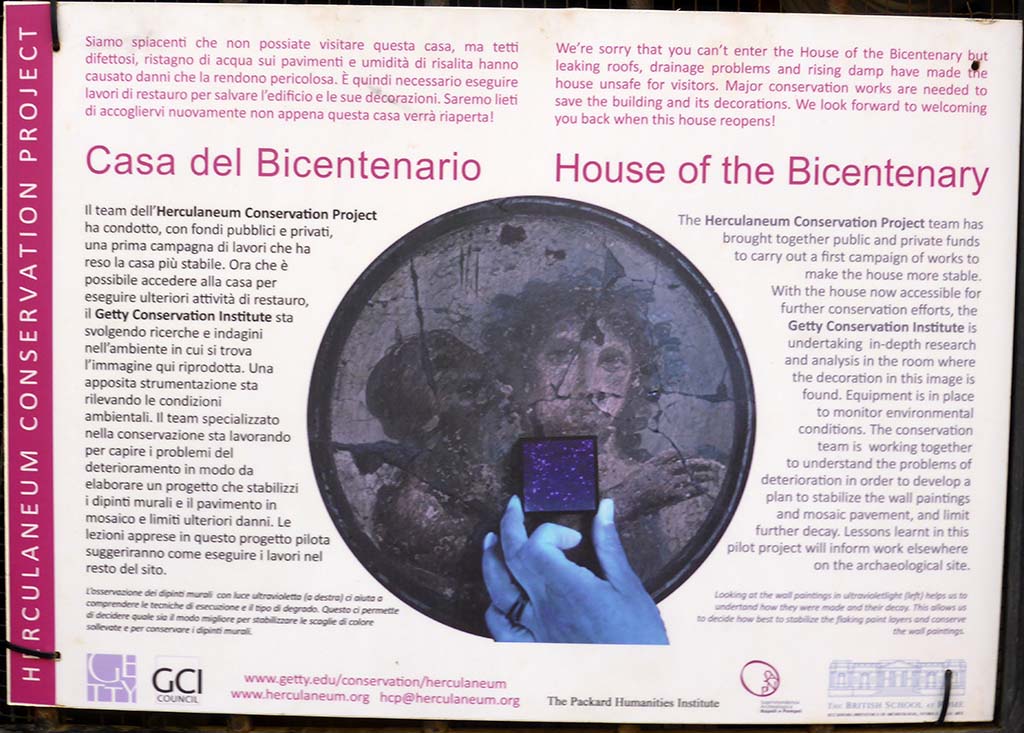

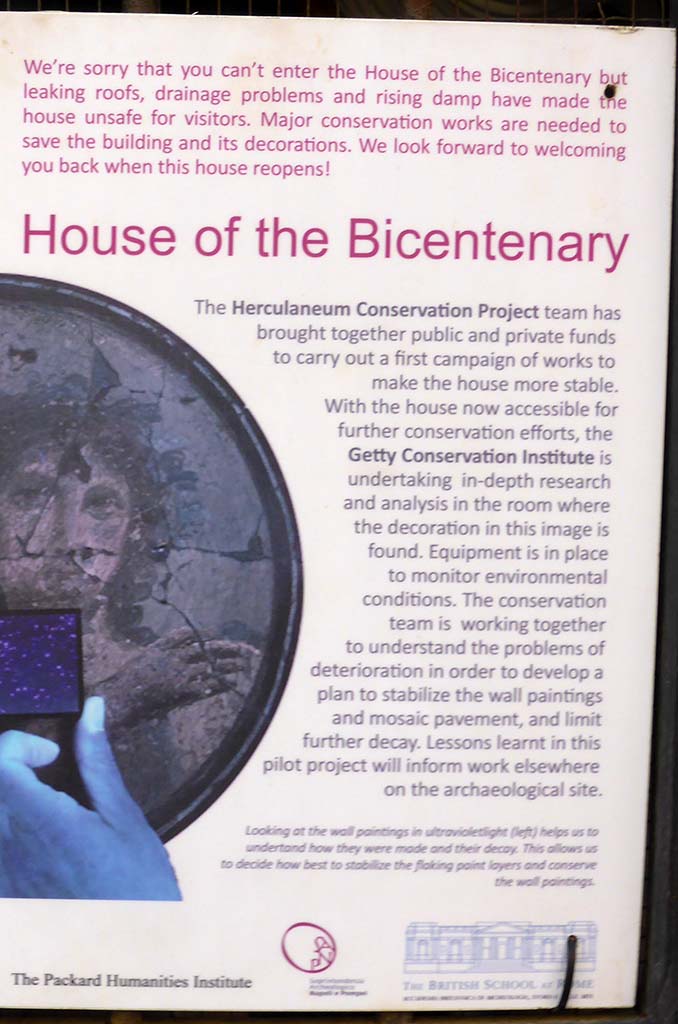

V.15 Herculaneum, September 2015. Information noticeboard.

“We’re sorry that you can’t enter the House of the Bicentenary but leaking roof, drainage problems and rising damp have made the house unsafe for visitors. Major conservation works are needed to save the building and its decorations.

We look forward to welcoming you back when this house re-opens”. (Re-opened to visitors, October 2019).

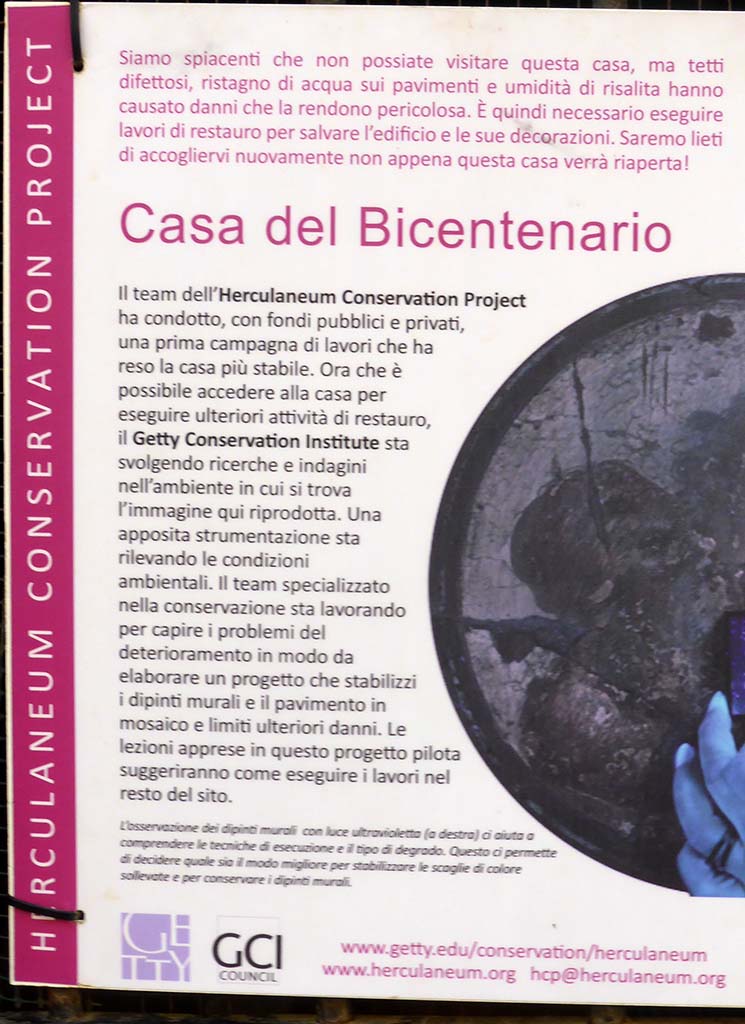

V.15 Herculaneum, September 2015. Italian half of information noticeboard.

V.15 Herculaneum, September 2015. English half of information notice displayed on entrance doorway.

V.15 Herculaneum, June 2012. Looking towards entrance doorway. Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

V, 15, Herculaneum, May 2010. House of Bicentenary entrance doorway.

V.15 Herculaneum, May 2010. Upper floor of House of Bicentenary.

The window above the doorway (no.14 on the right of the photo) would have given light into a room in which the waxed tablets of Calatoria Themis widow of C. Petronius Stephanus were found in a carbonized wooden box.

The contents of the tablets were still readable and recorded the process of “ingenuitas” (proof of being born a freedwoman) of Petronia Iusta, a girl born of Petronia Vitalis, a slave who was then freed by Petronius Stephanus.

Plaintiff - Calatoria Themis, widow of Petronius Stephanus

Defendant - Petronia Iusta, daughter of Petronia Vitalis

The case had been brought to contest whether Iusta’s mother had still been a slave or a freedwoman when she gave birth.

Plaintiff’s grounds - that Iusta had been born while Petronia Vitalis (Iusta’s mother) was still a slave, and therefore Iusta was a slave.

Defendant’s grounds - that Iusta had been born after the manumission of her mother, and therefore was also a freedwoman and entitled to inherit her mother’s assets.

History of the case –

Around the year 62AD, a baby girl named Petronia Iusta was born in the household of Petronius Stephanus, the mother’s name was Vitalis, but the father’s name was unknown or at least not recorded. Vitalis had been bought as a slave by Petronius. His wife was known as Calatoria Themis, herself a freedwoman.

Eventually Vitalis became a freedwoman, and as such assumed her master’s name and became Petronia Vitalis, the child Petronia Iusta was brought up in the family home by Petronius Stephanus and his wife Calatoria Themis, but definitely known to be illegitimate and not their own child.

After a while Petronia Vitalis decided to leave the household, as she and the wife Calatoria were not getting on. As a freedwoman she was entitled to do this.

She worked hard, was comfortably off and had made a good home for herself, but her master and his wife refused to relinquish Iusta.

As the child had been brought up like a daughter, she was regarded as an asset to the household.

Because of this, Petronia Vitalis started a court-case against Petronius Stephanus, as she wanted her daughter back.

This earlier court-case was resolved by Iusta being returned to her mother providing that her mother made a payment to Petronius Stephanus for all the food and costs that he had spent on the child during her childhood and teenage years.

Petronia immediately made the payment and Iusta was returned to her.

This would have been the end of the matter but all too soon Petronia died, and so did Petronius Stephanus.

His widow then brought another court-case to recover Iusta, as well as the considerable assets that she had inherited from her mother.

The case was brought on the grounds that Iusta had been born while Petronia Vitalis was still a slave, and therefore Iusta was a slave.

As slaves had no property rights, if Iusta was judged to be a slave, then all that she owned would have been returned to her mistress.

The case was brought before the local Herculaneum magistrates, who decided they lacked jurisdiction over the matter, and the case would be transferred to Rome.

Even in Rome the case became bogged down, until a new witness was called. He was Telesforus, who had served Petronius for many years.

He said he had handled the negotiations for the return of Iusta to her mother, and it was acknowledged then that Iusta had been born after the manumission of her mother. He said the Roman court should now make the same acknowledgement.

However, the Roman court were not prepared to reach a hurried decision.

The depositions to Rome had begun in AD 75 and AD 76, and it seems that by AD 79 when Vesuvius erupted and buried the tablets, a decision had still not been taken and nothing further has been found as to the outcome. Was Iusta declared free, or once again returned to slavery?

Perhaps they were lucky enough to be in Rome contesting their court-case in AD 79, or perhaps the tablets belonged to someone found as a skeleton in the seafront boatsheds. We shall never know.

See Deiss, Joseph J, 1968: Herculaneum, a city returns to the sun. London, The History Book Shop, (p.71), who mentioned 18 wax tablets.

See Guidobaldi, M.P, 2009: Ercolano, guida agli scavi. Naples, Electa Napoli, (p.90) in which 150 wax tablets are mentioned.

See Maiuri, Amedeo, 2008: Cronache degli scavi di Ercolano, 1927-1961. Sorrento, Italy: Franco di Mauro Editore, (p.91-98), mentions 18.

See Cooley, A.E. and Cooley, M.G. 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum; a sourcebook. U.K. Abingdon, Routledge, 2nd ed. (p.215-218, G5-11 in which 18 writing tablets are mentioned found in a chest).

Wallace-Hadrill wrote – “The story has been told many times, but we still await the new edition by Giuseppe Camodeca, which, to judge by his patient and skilful re-readings of so many other documents, may put an entirely new complexion on the story”.

See Wallace-Hadrill, A. (2011). Herculaneum, Past and Future. London, Frances Lincoln Ltd., (p.144).

V.15 Herculaneum, in centre. 7th August 1976. Upper floor of House of Bicentenary.

Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer, from Dr George Fay’s slides collection.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Plan of upper and lower floors